Thousands of soldiers from the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan are re-entering civilian life with invisible wounds: some with post traumatic stress disorder from killing or witnessing death and dismembering injuries, but also with moral injuries, which may be hidden or medicated with alcohol and drugs, and which require different treatment approaches than fear based trauma.

Some returning soldiers feel the guilt of surviving due to luck and state of the art medical intervention, experiencing that good luck as a betrayal of buddies. Others feel culpable for the loss of soldiers they have commanded and whose backs they covered, even if the actual cause of death was bad luck. One 19-year-old Marine, who served in Fallujah and Marja, said, “They’re all like little brothers who I trained.”

Others feel shame or helplessness about deaths occurring while they were absent, believing their presence could have prevented the deaths. For others the sense of moral betrayal is a sense of the awful costs of wars poorly conceived and unending. For them there is work finding meaning in experiences of wars that have come to feel futile.

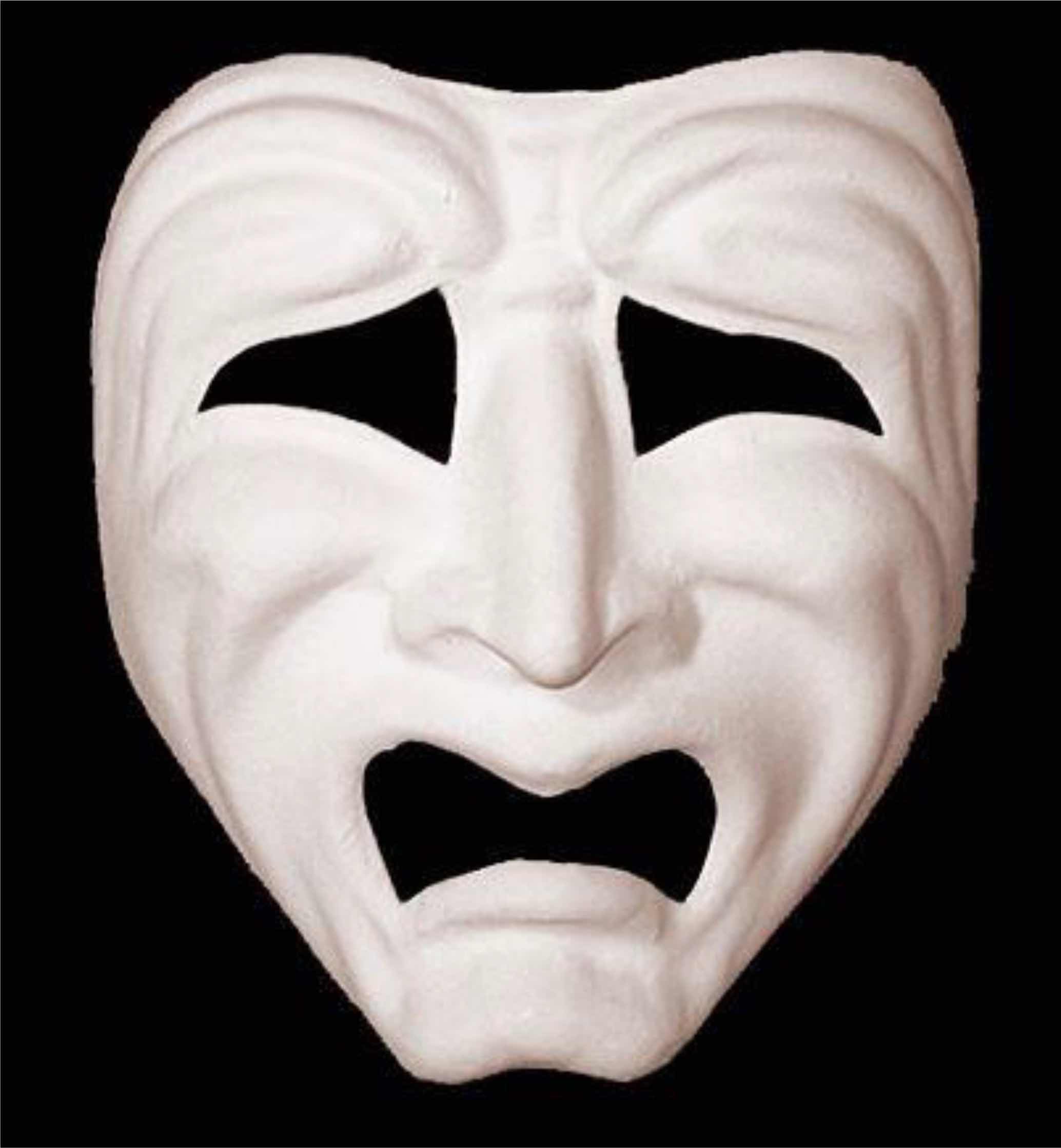

Civilians have a role in the healing of moral injury by engaging with soldiers beyond the thin crust of “Thank you for your service.” At the heart of civilian-veteran dialogue is the creation of safe places to talk, for example, watching and reacting to a drama about war such as “Ajax” by Sophocles. It is not easy to tell those who have not been to war about war, not only because of the blood and gore, but because of the feelings evoked.

Engaging with soldiers in their struggle to understand the moral contours of their experience in war honors our moral obligation incurred in sending them to war.