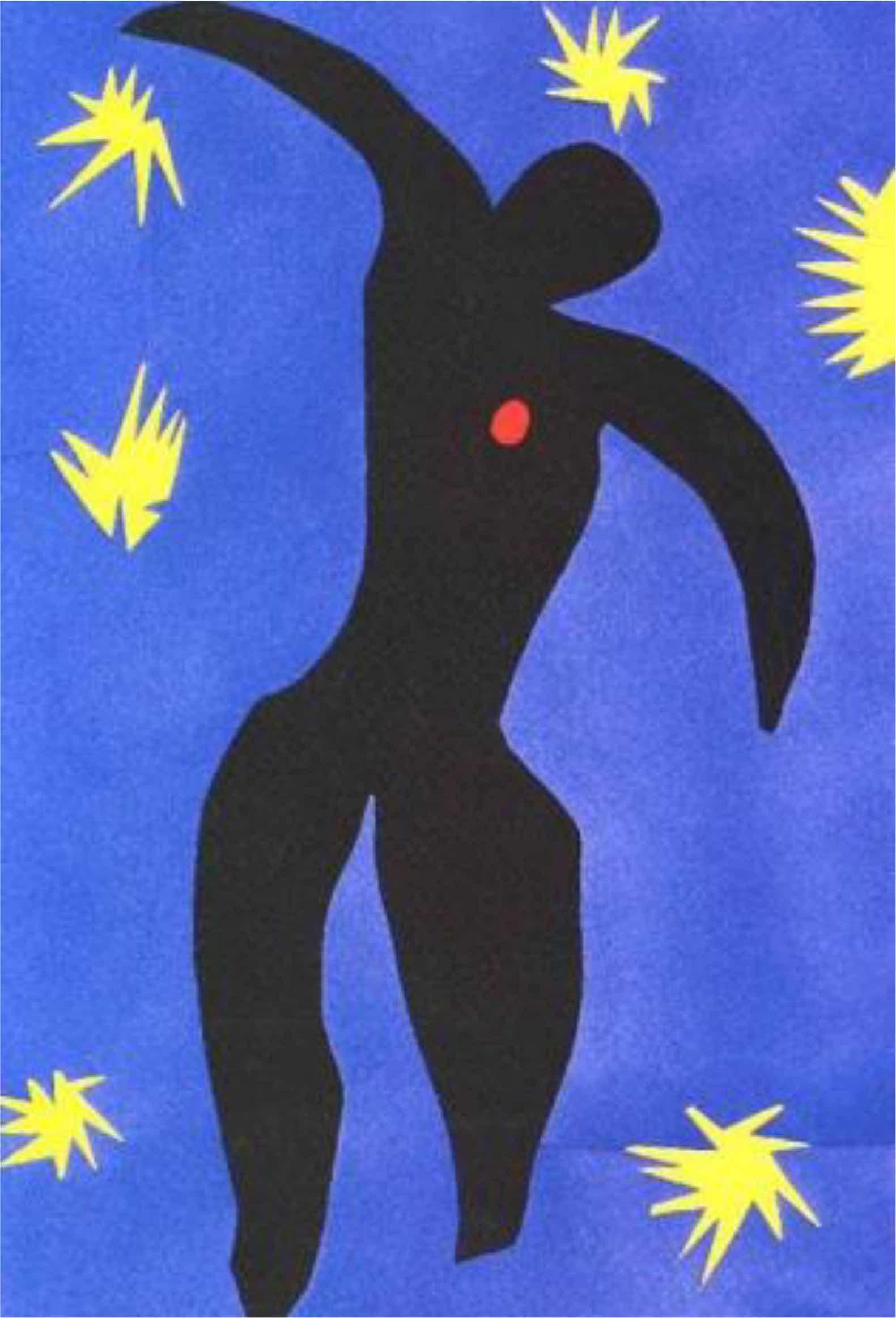

Henri Matisse called painting a “joy” and considered it his “cure” for mental distress. When his age barred him from the trenches of World War he was overcome with guilt and shame:he said, “a man not at the front is good for nothing.” At this time of monstrous carnage, he still felt drawn to the sensual in his art, but also morally repulsed by it. He became paralyzed, totally unable to paint. When he did return to the easel he found what he called “serenity” through a new approach to painting.

This approach, as Matisse describes it, echoes the essence of psychoanalytic therapy:over time the therapist seems to contain one’s inner life so completely, and to mirror it so coherently, that one feels comforted, as if reassured by an ideally empathic mother. Matisse found a similar bond with his canvas:he reworked the image repeatedly until it mirrored all his feelings and fantasies. This image reflected his inner tensions (his “opposing polarities”), but he created a “synthesis,” a harmonious image that reconciled these tensions. Like the patient with the therapist Matisse identified with the wholeness and harmony of the painting (“the artist and the painting are one”). He said when a painting was complete it made him feel calm.

For generations, psychoanalysts have “interpreted” art, but Matisse shows how art can provide us a new view of psychoanalytic work with patients.